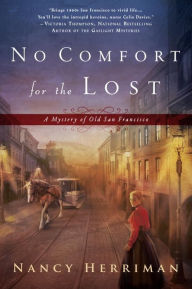

No Comfort for the Lost (A Mystery of Old San Francisco), Nancy Herriman (Obsidian, August, 2015)

Cover designed by Daniela Medina; Cover art by Juliana Kolesova

Book one of the in the Mystery of Old San Francisco series, 360 pp. At the time of this review (4/10/17), it holds a 4.6-star review on Barnes & Noble.

Historical Fiction, Mystery

Book Obtained By: Purchased at Westerville Public Library’s Author Fair, 2016

My Chocolate Rating on Scale of 5: 3.5 Reese’s Peanut-Butter Eggs, Hearts, or Trees

From the jacket

“In this atmospheric historical mystery series debut, a courageous nurse and a war-scarred police detective in 1860s San Francisco champion the downtrodden and fight for injustice….

“After serving as a nurse in the Crimea, British-born Celia Davies left her privileged family for an impulsive marriage to a handsome Irishman. Patrick brough her to San Francisco’s bustling shores, but then disappeared and is now presumed dead. Determined to carry on, Celia partnered with her half-Chinese cousin, Barbara, and her opinionated housekeeper, Addie, to open a free medical clinic for women who have nowhere else to turn. But Celia’s carefully constructed peace crumbles when one of her Chinese patients is found brutally murdered…and Celia’s hotheaded brother-in-law stands accused of the crime.

“A veteran of America’s Civil War, Detective Nicholas Greaves is intent on discovering the killer of the girl, whose ethnicity and gender render her as powerless in death as they did in life. Nick’s efforts are complicated by Celia, who has a knack for walking into dangerous situations that might lead to answers…or get them both killed. For as their inquiries take the from Chinatown’s squalid back alleys, to the Barbary Coast’s violent shipping docks, and to the city’s gilded parlors, Celia and Nick begin to suspect that someone very close to them holds the key to a murderous conspiracy….”

Review

No Comfort for the Lost (Obsidian, August, 2015) is book 1 of Nancy Herriman’s Mysteries of Old San Francisco.

Herriman tells this tale in third person, alternating POVS between detective Nick and nurse Celia, typically several shifts per chapter as Herriman tells the story in parallel—since Celia and Nick are both invested in unraveling the truth of the murder. Celia’s motivation stems from her work with the Chinese prostitutes; Nick’s, as he atones for a past loss—even though his captain makes no bones about the low worth of the Chinese, with a prostitute absolutely at the bottom of the barrel. Herriman paints the racial tension throughout the book, bringing it close to home with Celia’s half-Chinese younger cousin for whom she is the Custodian. How eerily familiar this tension became when I considered Donald Trump’s harsh language during the campaign, and after, against Mexicans and Muslims. Language always matters. Hats off to Herriman for making me feel anxious for the Chinese laborers and prostitutes, and anyone (like Nick and Celia) who tried to help them. That pervasive atmosphere added to the tension throughout.

Rich details of the era build the setting, from the Ladies Society of Christian Aid to the Anti-Coolie Association; from the saloons and brothels to medicines like “laudanum” and visits to the local apothecary or the astrologer and descriptions of outfits, like when Celia wears “her garibaldi and Holland skirt… (p. 141). Dialogue, too, hearkened back to an earlier era enough to lock me into an 1860’s town, such as “Change the dressing every day. … This is quinine. She must be given a grain every three to four hours.” (p. 5). I had no doubts that the author had read clips from San Francisco history, whether it was books or old newspapers.

For a mystery, Herriman wove in plenty of red-herrings, leaving me changing my mind every other chapter as to who committed the murder. Mixed in among this quest to solve the mystery, the everyday life, making me a part of Celia’s small family. From house-keeper Addie to orphan Owen, to Celia working with patients, to Celia trying to also solve the mystery of whether her husband has abandoned her, or whether he’s dead, the secondary cast round out that slice of life.

Part of the reason I’ve likely given this a “3” rating is that I can’t say I’ve read historical fiction since reading works authored in the late 1800s; my last was more an alternative historical fiction with a paranormal element (Mary Robinette Kowal’s Ghost Talkers). Another is the number of times the third person pushed me out, what are called filtering words. Take these sentences (bold my own): “The wound began to bleed again, which she took as a good sign.” Then, a few paragraphs later, “Celia stared at the empty doorway, saw a drunk laborer shuffle past and down the hallway, heard the call of prostitutes.” (page 5) In a tight third-person, the first sentence shortens to “The wound began to bleed again, a good sign.” The second, “A drunk laborer shuffled past the empty doorway. Down the hallway, prostitutes called out promises.”

A teacher could easily assign this book as part of a historical unit–no sex (outside of the line I quoted above, the only other reference is that there are prostitutes), violence in limited doses (and nothing gratuitous), and the first blush of romance between Celia and Nick makes me say this is historical mystery, not historical romance. References to drugs, from the ones apothecaries used to opium, would help students frame a dialogue about drugs of the past and drug issues in our day.

Book Cover of the second book in the “A Mystery of Old San Francisco” series

If historical mysteries are your thing, why not take a look? Then, if you enjoy this book, you might like Herriman’s next book in the series, No Pity for the Dead.

Learn more about Nancy Herriman: